|

Reprinted from ANTIQUES, January 1968, pp. 109-113

Vigèe Le Brun's Portraits Of Men

BY Ilse Bischoff

Vigée Le Brun's Home Page | Index to Art Pages

Vigée Le Brun's Gallery | Vigée Le Brun Biographies

MARIE LOUISE ELISABETH Vigèe-Lebrun (1755-1842), who reached the height of her popularity between 1779 and 1789, is known especially for her portraits of women, and as the favorite painter of Marie Antoinette and her court (ANTIQUES, November 1967, p. 706). Her portraits of men are less familiar, and it is sometimes with surprise that a gallery-goer, coming upon one of her strong male likenesses, realizes that she was as talented at depicting masculine virility as she was at rendering soft, beguiling pictures of feminine beauty.

When painting men she was not concerned with flattering her subjects. Here she did not confine herself to the young and pretty, although all of her portraits are elegant in composition and execution. One of her rules for posing men was that they should stand briefly on the threshold of a room so that she could judge the characteristic posture and the placement of the head on the shoulders. There is no evidence that she found it necessary to compliment men as she did women, to tell them they were handsome, that they posed well, or to put them at their ease in order to bring out the best in them. Often in her portraits of men the drawing is stronger than in those of women. She does not ignore the lines that age has left, and she includes an indication of character which she avoided in her feminine portraits. The hands of the men are better drawn and they seem to

relate to the faces. Her women's hands are apt to be carelessly constructed; sometimes they are undersized and boneless. Those in her portraits of the painters Claude Joseph Vernet (Fig 3) and Hubert Robert (Fig 4) and of the composer Giovanni Paisiello (Fig. 9) show that these men worked with their hands, while those of Charles Alexandre de Calonne (Fig. 6) and of Joseph Hyacinthe FranÁois de Paule, Comte de Rigand de Vaudreuil (Fig. 2) betray the fact that the subjects never labored manually.

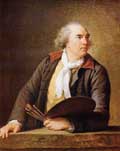

At the beginning of Vigèe-Lebrun's career, when she was studying the masterpieces at the Louvre, she was already well enough known to be asked by members of the aristocracy, visiting foreigners as well as French men and women, to do their portraits. It is difficult to establish the identity of her portrait of "Comte Shuvalov" (Fig. 1), done in 1775, since two Shuvalovs came to Paris fairly frequently during the third quarter of the eighteenth century. One was Ivan Ivanovich, not a count, although occasionally called one, who is often confused with his nephew Comte Andrè Petrovich. However, Vigèe-Lebrun notes in her memoirs that she painted Shuvalov in 1775 when he was about sixty, and since Ivan Ivanovich was forty-eight and his nephew was thirty-one at that time, it seems more likely that it was the former who was portrayed. He was a friend and correspondent of Voltaire and a patron of the arts who founded the University of Moscow. This portrait shows the artist's skill at drawing at an early age; the head and body are solidly painted and the textures of fabrics are rendered with sensitivity.

Vigèe-Lebrun's glowing tribute to the Comte de Vaudreuil in her memoirs, written when she was well into her eighties, leads one to the conclusion that he was more to her than just a friend. She thought him a paragon among men. He was handsome, well built, and carried himself with elegance. He combined courtesy with gallantry; his manner was gracious. Witty,

gay, an excellent raconteur, a patron of music, and a collector of the finest paintings, he was a man whose spirit was the best the eighteenth century had to offer. Comte de Vaudreuil's own admiration for Vigèe-Lebrun, both as a painter and as a woman, steadily furthered her career. Her paintings hung in his sumptuous houses, and some of the most brilliant and famous people of Parisian society came to her house because he helped spread her name among the great families of France. In her ambitious climb upward from poverty to fame, his friendship was invaluable. Vigèe-Lebrun's large portrait of him (Fig. 2) is a pleasing one, although in it he seems posed and she has not caught the ease and grace that so impressed her. Nor does it entirely convey the virility for which he was famous. However, her portraits of the Comte de Vaudreuil were so popular that in one year she painted six for the many friends who wanted his likeness. Able as the painting is, it does not quite rank with her best of men.

Vigee-Lebrun had her own salon, like other ladies of her day, which was frequented by writers, artists, and musicians, as well as by the nobility. Among those who gathered there were Claude Joseph Vernet, Hubert Robert, and the composer Andrè Ernest Modeste Grètry.

Vernet, who had been commissioned by Louis XV to paint the harbors of France, was among Vigèe-Lebrun's best friends. He had immediately recognized the potential of her talents and encouraged her throughout his life. It was he who gave her the advice all good teachers give serious art students: "Do not follow any system. Study the works of the great Flemish and Italian masters. Above all study nature. She is the best master and if you will be true to her you will not develop mannerisms." In her sympathetic portrait of him (Fig. 3) Vigèe-Lebrun has depicted a warm-hearted man with gentle brown eyes. Since she was not seeking to flatter here, she captured the personality of a living human being who meant much to her.

Possibly the most outstanding of Vigèe-Lebrun's portraits of men is that of Hubert Robert, painted in 1788 (Fig. 4). Robert was a landscapist and painter of idyllic ruins, fountains, and temples remembered from his student days in Italy. Back in his native France he idealized these ruins for decorations in Madame du Barry's palace and those of other famous people. His facility with the brush was machinelike. He could, his loyal friend Vigèe-Lebrun noted, dash off an exquisite painting in the time it took another to write a letter, in an age when letter writing was as easy as breathing. Her portrait of him, which ranks among her finest, is very masculine, and shows the influence of her beloved Italian masters. Strong in color, it is executed with affection for the man, with the rapport necessary between painter and subject to achieve ultimate perfection.

Andrè Grètry (Fig. 5) often sang or played his compositions at Vigèe-Lebrun's salon before they were publicly performed, and his operas and music delighted Paris. Born in Belgium, he received the major part of his training in Rome, and later went to Paris where he established himself after 1768 as the leading composer of comic opera.

One of Vigèe-Lebrun's best-known portraits is that of Charles Alexandre de Calonne (Fig. 6 ; see ANTIQUES, May 1966, p. 707). In her memoirs she does not deal kindly with Calonne, perhaps because it had been rumored that she was his mistress, and even when she was in her eighties the old scandal still rankled and annoyed her. In her portrait of him the light red brocade of the Louis XV armchair and of the drapery, his elegant costume, and the still life of inkwell and quills are as expertly rendered as all details in Vigèe-Lebrun's portraits. After his fall in 1787 as comptroller general of finance, Calonne settled in England, though he was allowed to return to France in 1802, the last year of his life. An avid collector of paintings, he took his collection to London where much of it was sold. Vigèe-Lebrun's portrait, signed and dated 1784, was bought by George IV in 1806 or earlier, and was recorded at Carlton House in 1816.

Vigèe-Lebrun's husband, the astute picture dealer Pierre Lebrun, usually determined her fees, collected them, and then doled out whatever money she needed. Only once before her flight from Paris in 1789 during the early days of the Revolution does she seem to have collected her fee herself, and that was for her portrait of Emmanuel de Crussol, Duc d'UzËs, which now hangs in the Metropolitan Museum of Art (Fig. 7). The duke appears to be a man in his forties with a proud, handsome face.

The early summer of 1788 was warm, beautiful, and outwardly calm. While Vigèe-Lebrun could still travel in safety to Romainville to paint the Marquis Philippe Henri de Sègur, a marshal of France who had been minister of war from 1780 to 1787, she noticed that the peasants no longer doffed their hats to her; there was tension in the country which was spreading into the estates lying outside of Paris. The Marquis de Sègur lived in retirement while France hurtled toward disaster. This portrait (Fig. 8) shows a man of dignity, pride, and a touch of arrogance. He is posed in such a manner that the spectator is not immediately aware that the left sleeve is empty; the arm had been shot away at the battle of Laufeld in 1747.

During her voluntary exile from France during the Revolution, Vigèe-Lebrun painted throughout Europe. One of her most successful portraits of men was painted in Naples soon after she left Paris -- that of Giovanni Paisiello, the famous composer (Fig. 9). It is not known whether she was asked to paint him or whether she requested a sitting. The portrait, now in the Louvre, was bequeathed to the museum by Vigèe-Lebrun's niece, who

had inherited it from her aunt. It is a strikingly well-designed picture of a man at his instrument, possibly in the very act of composing. Vigèe-Lebrun has not sought to paint an overly idealized portrait; she has painted the rather ordinary-looking, stocky, well-fed man she saw before her.

In 1795 Vigèe-Lebrun left Austria, where she had been an enormous success for three years, and traveled to Russia, where she remained for six years. Catherine the Great had eagerly awaited her, but the portrait of Catherine's granddaughters failed to please the

Empress, and Vigèe-Lebrun did not enjoy royal patronage. However, St. Petersburg society took her up, as had society everywhere in Europe. Rostopchin, later governor of Moscow, commenting on her tremendous vogue, wrote that she received one to two thousand rubles a month for a portrait, for which, in London, she would have been paid only two guineas. During her stay in St. Petersburg she met Stanislas Augustus Poniatowski, former King of Poland and lover of the Archduchess Catherine before she became Empress. They became great friends and Vigèe-Lebrun painted the strong, compassionate-looking man, with white hair and a ruddy face, wearing the robes of state (Fig. 10).

After a brief return to her native land in 1802, her name at last removed from the list of èmigrès by a petition signed by prominent men and women of the Consulate, Vigèe-Lebrun went to England for three years. She had not been able to adjust to life in Paris under the Consulate. In her own country, even after what could only be called an artist's triumphal tour of Europe, other painters were now in vogue, and her kind of painting was too old-fashioned and too closely related to the ancien règime to be in demand. She hated England, but she found there the appreciation so necessary to her. She joined the circle of French exiles and found many of her old friends. Among her English sitters were Byron and, the prize catch of all, the Prince of Wales, later George IV. She returned to France in 1805 and remained there until her death in 1842 except for a visit to Switzerland in 1808 and 1809, where she painted Madame de StaÎl. Her work during the last forty years of her life did not compare with her portraits of the 1780's and 1790's; she had reached her height before the middle span of her life and had not grown as an artist since achieving the summit of her talent in 1789. It is regrettable that of her known paintings so few, relatively, are of men.

Vigée Le Brun's Home Page | Index to Art Pages

Vigée Le Brun's Gallery | Vigée Le Brun Biographies

|